Series Order:

1. Busting God

2. Remains to be Seen

3. Stella by Starlight

4. No Through Road

5. The Real Thing

6. Trio: Three award-winning stories

7.Transference

8. Last Train to Parthenia

9. The Cyborg’s Story

10. Reflections

1. Busting God

I loved the work too well. That was the problem. Even sitting in my kitchen nursing two cracked ribs, the contents of the house trashed around me, I still loved it.

But I was growing older.

I watched what I ate. I sweated at karate and ran miles every day so that I could stay in the field.

Still I grew older.

Reg Mulcahey was leaning against my kitchen sink, looking worried. He pulled a packet of Camels from his pocket, lit two and passed one to me.

“Why didn’t you tell those cops you were a narc? Christ, Michael!”

I opened the freezer and pulled out a packet of frozen peas I’d intended to use in the Pritikin tuna and vegetable casserole that night. I sat down and held the packet against my rapidly closing eyelid.

“What’d you expect me to do, Reg—blow a cover I’ve been working on for months?”

“Well, y’ cover’s blown now,” Reg drawled. “I had to show them my ID to get them off you. They can send someone else into that nightclub. By the way, The Eagle wants to see you. That’s why I came.”

The CEO had eyes that seemed to see right through you; that’s why we called her The Eagle. This afternoon she was in a hurry. She was due at a high-powered press conference on narcotics at two. She could barely make the time to tell me I was taking a paid trip to the Northern Rivers to bust a heroin dealer everyone up there called God. She threw my new ID papers at me and told me to catch the next train out of Sydney.

“Where exactly would you like me to go, ma’am?”

“If you’re meaning a town, O’Neill—try Murwillumbah.”

My clothes were torn and bloodied. I was still holding the packet of frozen peas to my eye. She didn’t seem to notice.

“I’d like to take Azure with me,” I ventured.

“Nix to that, you’re taking Johnson with you. Not on the same train, of course.”

I knew Baby Johnson from Vietnam. Everything he touched turned to trouble. I didn’t want to go anywhere with Baby, but it was no use arguing.

The peas had melted. I pitched them into her wastepaper basket and turned to go.

“O’Neill?” She got me just as I reached the doorway, a trick of hers. “When you come back—you do intend to come back, don’t you?—I expect you to take that desk job. Why don’t you marry that girl and settle down?” she hurled after me. “You’re too old for field work anyway.”

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00J8ZIE8S

2. Remains to be Seen

The doorman at the Ex-Services Club won’t let us in. “Sorry, sir,” he says to Baby. “It’s your T-shirt.”

“My T-shirt?!”

Baby stands six-foot-four in fishnet stockings, so the doorman pretends to defer a bit.

“Today’s the anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea,” he goes on, little knowing the danger he’s in, “and there’s a lot of the old fellows here tonight. They wouldn’t like it; wouldn’t like it one bit, that T-shirt.”

“What’s wrong with the bloody thing?” I ask like a man possessed. Beside me I can hear the psychic whine of Baby revving up to high gear.

“It’s got a rising sun on it,” the doorman explains patiently. “It looks Japanese. I can let you in,” he waves a hand at me, “but not him. Not in that T-shirt. Sorry.”

I drag Baby back to the parking lot and push him into the car. As I ease the old Holden through the rain suddenly I can see, through the flashes of lightning, that the lot is filled with Japanese cars—Toyotas, Mitsubishis with bull bars—you name it, the place is full of them.

I slam my fist down onto the dashboard, but Baby just throws back his head and laughs. He seems to find it terribly amusing somehow.

He’s still laughing as we drive through the slashing rain to David’s with four six-packs.

This fucking rain, will it ever stop? I can see it through the open door of the chopper, though I can’t hear it over the noise of the blades. We’re the third drop into the landing zone. It was supposed to be a combined effort with the Americans, but the Marines won’t go. I can hear the American CO on the radio threatening them with court martials and damnation, but they’re not under his jurisdiction and they know it. They turn, all seven loads of them, and head back to where they came from.

So long, Marines, thanks a lot.

They’re not so dumb: we’re going straight down into an ambush. Looks like we’re jumping right into the middle of the Viet Cong’s training field and they’ve been planning for just such a contingency for months.

Across from me in the chopper Billy The Kid’s throwing up; he’s green with fear—he’s also Baby Johnson’s kid brother. Baby’s on R & R leave in Sydney. It’s up to me to keep The Kid safe while he’s away. Baby’d probably frag me during a raid if I lost him.

The gunships hover above us, hosing down the edges of the clearing. They pull up and we’re landing. Our door gunners let go one long burst and we run, heads down, for the trees.

The trees here are very different, unless you go right up into the mountains into rainforest country; and I don’t like rainforests.

Not anymore.

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/454352

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00LNDWRM2

* * *

3. Stella by Starlight – preview

On the day Charles Lawson planned to kill himself, the day he’d decided had the best chance of success, he rose at six as usual.

“Come on, Cynthia, time to get up.”

The old cat had slept all night on the end of the bed. Now she stretched and rose reluctantly. Lawson leaned over to pat her.

“Where’s Bruiser, Cynthia? Where’s that young cat?”

Charles Lawson pulled on cotton slacks and a shirt, put on his spectacles and ran a comb through his white hair without looking into the mirror. He had no use for mirrors anymore. In the kitchen, he opened the back door and called for the young cat.

“Bruiser! Yoohoo, Bruiser!”

When the young cat came in, spruce and self-important on the third call, he rushed straight to his bowls and began to wolf down the food. Charles Lawson watched him as he ate. This was Bruiser’s first summer and, although neutered, he’d taken to staying out in the evenings, which caused Lawson much anguish of spirit as he watched the clock through the night.

When the cats had been fed, he made himself a cup of ground coffee, with a generous dash of whipping cream and two sugars. Every nutrition book he’d ever read put coffee down, but since he’d decided on his Course of Action, as he called it, he didn’t see the point any more in giving up this small pleasure.

The sunlight shone into the living room through the banana trees in the front garden. Lawson sat there with his coffee and reviewed his plans. With luck, he thought, there wouldn’t be an autopsy, and even if there was, well, they’d be expecting to find rum in his system—though not that much.

“So,” his daughter Dorothea had said when he’d told him, during one of their phone conversations, that he’d adopted the habit of having two nips of rum with Coca Cola every evening, “you’re on the rum now, are you, Dad? Hope you don’t get onto it like Great-uncle Arthur used to!”

They had laughed at that, although Arthur Lawson’s rum drinking had not been a laughing matter in his youth.

“Sometimes, Thea,” Lawson had pretended to confess during that particular phone conversation, “I even have three! It seems to help my arthritis, you know.”

By this ploy, Charles Lawson hoped to escape detection as a suicide. Suicides always cast such gloom over funerals, and he wanted an elegant one. Besides, the mourners would think he’d been depressed. “Poor thing, I didn’t know he was depressed—did you?”

Lawson didn’t feel at all depressed. Now that he was out of jail, he was happy with his life the way it was, and with the small triumphs of his day: getting the garbage out unaided, managing the back steps, walking to the nearby beach and back.

Things had been good. Until that visit to the eye specialist.

Macular degeneration, she’d called it. Irreversible. With the cold logic of surgeons, she had explained the progression of the disease and the likely time remaining to him before he was totally blind.

If only she hadn’t used that word totally, Lawson thought. He couldn’t adjust to totally. And what then? Would he have to go to Perth and live in a granny flat in his daughter’s back yard like what’s-his-name in Scent of a Woman? Blind at eighty-two when you were too old to adjust?

Ah, no.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00MTVVG9C

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/467119

* * *

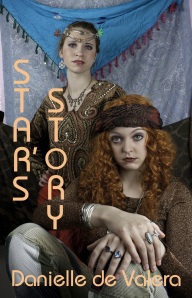

4. Star’s Story – preview

I didn’t look in the mirror as my hair fell around me, the hair my father had loved so much. Perhaps the impulse to cut off my hair was brought on by the anaesthetic.

“Have you got someone to take care of you when you get home?”

“Yes yes, I’ll be fine.”

My face looked pale under the fluorescent lights. My eyes revealed too much. I looked down, studied my designer mini-skirt, my sheer pantyhose, my Italian high-heeled shoes. They’d have to go.

The whole effect had to go.

“There,” the hairdresser said, dabbing at the back of my neck with a soft brush.

Bought a pair of Baxter’s at a nearby shoe store. Bought a pair of jeans, a denim cap and two shirts at St Vincent de Paul’s and changed my clothes in the cubicle, leaving the designer gear behind me.

When the north bound XPT pulled into Central, I was the first person on it. I’d bought a ticket to the end of the line, Murwillumbah, but I figured I’d jump off wherever took my fancy. The train slid out of the station. The whole mess was behind me.

After dinner the lights came on in the carriages. I took the two sleeping pills the doctor had given me and slept, without dreaming, through the night. When I woke, late in the morning, the train was pulling into a small country town. Two horses stood in a paddock near the shunting yards.

The station sign slid by, black print on blue.

M U L L U M B I M B Y

I walked up the main street to the Top Pub, carrying nothing but a shoulder bag.

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/479505

* * *

5. The Real Thing

Well, Lawson thought, forget what you’ve seen on TV and all those National Geographics. Central Australia was boring— just red soil, scrubby trees and rocks. He couldn’t see what the fuss was all about. But he was weary of his life in Sydney, his suburban life with Angela-and-the-kids; he was glad to get away for a while. And then, of course, there was the money.

The Science Centre, so hi-tech for 1960, loomed in the fierce sunlight as he crossed the tarmac from the plane to Reception, the bitumen soft under his feet. Already he was beginning to have misgivings. As far as the eye could see, the place was fenced and topped with barbed wire. And all this security was for what? So the Brits could drop a few bombs? He took the crumpled telegram from his pocket, smoothed it out and read it again:

Come to Maralinga STOP Will make it worth your while STOP

Ben Landy.

Lawson hoped Landy would make it worth his while. Aging academics with expensive tastes needed all the lucre they could get.

The Science Centre’s vestibule was deserted except for the guards on the doors. So much security, Lawson thought. As if anyone in their right minds was going to go out there unless you paid them.

He dumped his bags, went over to the reception desk and leaned on the buzzer. No one came.

The vestibule was full of lounge chairs and coffee tables — no sofas. Lawson sat down in a club chair near the fake waterfall, leaned his head on his arms and tried to breathe through his post-flight nausea. It had been a rough trip in a Fokker Friendship; air pockets all the way from Sydney.

Just as he was beginning to pass out, a young man in his mid-twenties came into the room through one of the internal doors. He was wearing a khaki uniform and boots. His hair had been dyed a beautiful shade of copper. He had green eyes.

‘Why didn’t you buzz?’ he demanded.

Lawson had a sudden memory of wanting to become invisible at will. He’d been eight at the time, spending his pocket money on fake spilled-ink blots off the back pages of the comics, skeletons on strings, watches with luminous hands and dials (read in the dark! such a marvel), fake dog turds. If only he’d known. Why, all you had to do was dye your hair grey; you didn’t have to do anything else.

Lawson bestirred himself, patting at that iron-grey hair — should he have dyed it? He was only forty. He pulled himself back from this dilemma to answer the stranger.

‘Thanks for the welcome. It’s touching.’

The young man’s eyes flashed. Lawson got the feeling they weren’t going to get on.

‘You,’ he said (Lawson didn’t like the way he said the you), ‘must be Charles Lawson.’

‘Doctor Charles Lawson,’ he replied. His ID didn’t seem to impress the stranger.

Lawson studied the copper-haired apparition from under the brim of his hat. His days of chasing young men were gone—besides, this one was too young. And far too beautiful.

And the longer he stayed, Lawson thought grimly, the better looking the boy would get.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00OQAB7UW

https://www.smashwords/com/books/view/485352

* * *

6. Trio: Three award-winning stories

You don’t hear the thud when your head hits the door frame. You feel it.

When he puts his hands around your throat, you don’t hear the sounds you make as you struggle for air.

Later, examining your face in the bathroom mirror, praying there won’t be something showing that you can’t disguise with make-up, you don’t feel anything much. Just apathy.

You’re walled into apathy like someone in a tomb.

When people come to the front door you don’t answer when they knock. You hide.

When you go shopping, sometimes you have to wear a scarf and dark glasses. And long sleeves.

When your best friend tries the front door and you don’t answer, she knows to come around the back. You’re hiding under the kitchen table, waiting for whoever it is to go away.

‘Christ!’ she says when she sees you. ‘Why don’t you leave him?’

* * *

7. Transference

It’s late when I get there, and any fool could tell you I don’t like the idea. I stand in the parking lot and look up at the building. It’s tall and glossy and glamorous in the inner city dusk. The sun is setting, and the windows on the west glitter like mirrors. Very pretty, if you like that kind of thing.

I push through the glass revolving doors into the foyer, tramp through the vestibule in my old motorbike gear, punch the button and wait for the elevator. My muscles ache and my split lip hurts. If it wasn’t for my lip I wouldn’t be here; but when you’re so bone tired from lack of sleep that a student can spit your lip . . . Did I hear the word sleep? I used to sleep like a log.

But that was before Azure left me.

The elevator climbs to the twentieth floor and stops. I step out into the corridor. There’s a brass plaque on the opposite door. It reads:

DR A. WEST M.D.

I run one fingertip warily over the brass. Very shiny, very nice. If you like that kind of thing.

The waiting room is the jungle scene from somebody’s movie. I beat a path through the palms and accost the secretary. She checks me out in her appointment book and waves me back to the jungle.

‘Snakes?’ I demand, waving at the undergrowth.

She smiles at me charmingly, all haute couture and silver jewellery, as if I’ve just asked her the time.

‘No. No snakes.’

‘If I see one, I’m leaving.’

‘I assure you, Mr Morrison, we have no snakes.’

I wrench a chair from a giant tree fern and sit down grimly. Some intrepid person has been here before me and left behind some magazines. I flip through them aimlessly, keeping one eye on the jungle.

What the hell am I doing here anyway? I feel ridiculous. Six months have gone by and I still can’t look at another woman, still can’t sleep properly at night, still fantasise about smashing Hugh’s head in — I would’ve too, if he hadn’t shot through to Perth the moment he made off with Azure. The bastard.

Azure, Azure, I am obsessed with Azure. But she’s gone. That’s my problem. I come back from my reverie. The door to Dr West’s office is open, and Dr West is standing in the doorway.

The time to take off is now. And yet, I need to talk to someone. If I don’t sleep properly soon, my rising career in the martial arts will be up the creek, down the drain, finito. Besides, it’s too late now, she’s seen me. There she is, gesturing to me through a gap in the foliage. I push aside my misgivings and wade through the carpet to her door, and this is where my troubles really begin.

* * *

8. Last Train to Parthenia

He found the amulet on a dark and drizzly night when the city seemed asleep on his way to work. His gang worked from midnight to dawn in the inner-city circle of StateRail, Sydney, walking these tracks trailing spot welding gear to repair any cracks they found in the rails. Mostly they were underground, walking miles every shift to ensure the safety of those thousands of commuters who entrusted their lives to StateRail every day.

Occasionally they found strangers in the tunnels: sobbing girls with bottles of vodka, waiting for the first early-morning train to despatch them; truculent men with similar intentions.

‘What happens to these people?’ Johnson asked Colin, the head ganger, after he’d encountered his first would-be suicide.

‘We take them back to the office. The manager gives them a dressing down.’

‘That’s all?’

Colin placed a hand on Johnson’s shoulder. ‘I think if they’re really ratty, someone calls the mental health team.’

How many people, Johnson wondered, used the railway to top themselves? StateRail didn’t advertise, never seemed to put out any figures.

Still, work on the tracks of the inner-city circle suited him. Although he was ten years older than the rest of the gang, he had no trouble with the miles they had to walk—he’d been walking miles at night for years, a legacy of his stint in Vietnam.

The concentration needed for the job suited him, too. It was almost a meditation: eyes on the rails, lights from their helmets flashing across the soot-encrusted walls of tunnels. Occasionally odd things happened that kept them on their toes—an unscheduled engine passing through, for instance. Although they carried mobiles to warn them of these trains, the reception didn’t always work. The gang had to be ready to get the welder off the rails at a moment’s notice, and hurry to the safety of the alcoves if they were in a tunnel, or a safety hole, if they were in the open.

The first time Johnson crouched in a safety hole with Colin, clinging to the safety rail, waiting for the train they’d been warned was coming, he found himself more frightened than he’d ever been in Vietnam.

‘Why can’t we go to a tunnel alcove?’ he’d asked Colin when he heard the train whistle at the approach to the tunnel.

‘Because you need to learn this, Bob,’ Colin said. ‘We’re quite safe here as long as you hold on to the rail real tight.’ The main danger with fast trains, he’d added, was that you could be caught in the slipstream and pulled under.

The train seemed to be bearing straight down on them.

‘Are you sure we’re in the right place?’ Johnson yelled to Colin.

‘Just hold on tight!’

The train thundered towards them. When he was certain they were going to be annihilated, Johnson saw it was on a path that took it beside, not over, them. The power of the slipstream was incredible, like an evil force that longed to drag them under. Johnson hung on tight to the handrail and prayed; he hadn’t prayed in a long time.

‘Still like working here?’ Colin grinned after the train had passed.

Johnson answered yes. But from then on he listened even harder for the unscheduled trains and engines that might use the inner-city circle during their shift. They averaged about two alarms of that kind a month.

* * *

9. The Cyborg’s Story

It was my job to watch, not to intervene. Bodyguards were rare on Earth in 2175, but Thurston must’ve figured the experiment of a lifetime needed protection; or maybe he just wanted a witness, I don’t know.

I watched on the monitor as he ushered her into the office. She was fragile and beautiful, very much the dancer. Her thick rich hair fell down to her waist. It was the colour of ripe maize. I sat in the cubicle, watching, listening.

Thurston was speaking with an undertone of excitement in his voice. ‘What you’re suggesting is incredibly dangerous, and the procedure would be irreversible. If I were inclined to do it, which I’m not.’ He leaned back in the antique wooden chair he insisted on using and looked at her over the top of his spectacles; he wouldn’t wear lenses. ‘You mightn’t survive the operation.’

The afternoon sunlight shone in through the stained glass windows of the old one’s study. I could see the dancer analysing the patterns they made on the floor — or was she analysing her chances?

Thurston pulled a pipe from his pocket and began to stuff it with the coarsely ground tobacco leaves that he bought on the black market and kept in a worn, round tin in the second drawer of his desk. An ancient habit, nicotine, so out of date and fashion that this alone would have revealed his great age. The dancer waited in silence. Soon the smoke reached her from across the desk, and I think she adjusted her sensors.

‘What about your wings?’ Thurston asked suddenly, as if he wished to catch her off guard. But she had prepared herself for this.

‘They’d have to go,’ she said simply.

Thurston shook his head. He was a small man with light bones, blue eyes and thick, silver-grey hair. His clothes were old-fashioned. He was considered eccentric. But he was the Director of Genetic Engineering and had been for more than twenty years. ‘Come now, Azuria.’

So that was her name.

‘What made you decide to come to me?’ he continued.

Azuria smoothed a fold of her cream-coloured robe. All flyers wore robes; there was a particular colour for each profession. Winged dancers always wore cream.

‘I know you can do it.’ Her voice was soft and clear, graceful as her robe. ‘I think I’ve always known.’

The old guy busied himself with some papers — another one of his weird habits: papers. I noticed his fine blue-veined hands tremble slightly and I read in him an undercurrent of something I couldn’t define.

The dancer was easy. She came straight to the point, and I wondered if she were malfunctioning. She was asking him to make her human. No wonder he wanted a bodyguard with a top security clearance. No wonder he’d made me the offer he had.

May I remind you, sir, that under Federation law the penalty for what she is proposing is death.

Thurston shifted another paper to acknowledge my message. He let Azuria think her proposal had surprised him. Yet he had known her request in advance. Why else had he asked for my services?

‘You’re the best winged dancer in the five districts.’ The tone of his voice invited her to confide in him. ‘Now why would you want to give that up?’

She lied. How do I know she lied? It’s my business. I’m an INFJ, an old term but still valid. My intuition levels are way above the norm and my judgments are ninety-three point five per cent correct. That’s the best you can buy, which is why old Thurston picked me, no doubt.

I inhaled two crushed crystals of off-world Blue Monday and watched her lie. Whatever she hoped to gain by persuading Thurston, she wanted very badly. The light passed from the stained glass windows, and still they talked. She strung words together like strands of pearls.

And in the end, the old man nodded his head.

‘She’s lying,’ I told him after she’d gone.

The blue eyes took on a steely glint. ‘Your people can’t lie, Michael. It’s not in their genetic programming.’

* * *

- Reflections

I hear them, you understand. And yet I don’t hear them. There’s really no point in listening; it’s the same thing every time.

“Good morning, Mr Lawson, and how are we today?”

Answering these girls is pointless. They aren’t really asking you a question — it’s a greeting, something to say. People have to say something to each other when they’re strangers.

I drink my cup of tea in silence and give thanks for small mercies. It tastes like dishwater but at least it comes. It’s something you can rely on.

The sun’s out today, so we get to sit in the garden between morning tea and lunch time. The trees here are very beautiful, and though I can‘t see well any more, I can tell there are lots of brightly coloured flowers in the garden.

“It makes the place look so cheerful,” Matron says. But of course you can’t pick them. When I had my own place, I always grew flowers as well as vegetables, always liked to have cut flowers in the house.

The painters are here again. Seems they’re always painting this building.

“‘Scuse us,” they say as they carry their ladders past me.

I don’t answer them.

“Wonder what he’s thinking,” says the dark haired one, the one who reminds me of my daughter.

“Prob’ly nothing at all,” the other one says. Coarser. Fairer. “You know what they’re like at that age.”

Let me tell you, BoyO, you won’t get to my age. If you do, you’ll be dotty—like Iris, who wanders the hallways, crying, “Don’t Daddy, don’t!” Or you’ll be drooling like poor old Colonel Henry, who used to command an entire regiment in the Second World War. How are the mighty fallen, And the weapons of war perished.

Then there’s Mrs Everton, who was a bank manager’s wife in a previous existence. She thinks she’s in the hotel her husband used to take her to when they were courting.

“It’s a beautiful place, Mr Lawson,” she says to me. “The gardener does a wonderful job. I think I’ll have my wedding reception here.”

“You do that, Mrs Everton,” I always say. Why burst her bubble?

Some days, though, I think something gets through to her. Those days she looks upset and spends her day staring out the window. When the nurses say wouldn’t you like to watch TV, she waves them away.

Everyone’s mad here but me.

Leave a comment